Love Tokens: Early Roots

Coins have been carried for luck for centuries and sometimes those coins were accidentally spent. In Great Britain it became common to mark the coin so this would not happen. As a result, “benders” were fashioned. The coin was twice bent, one side up and the other side down. This made it easy to both see and feel to distinguish it from other pocket change. Some benders marked a vow that was taken and others were tokens of affection or luck.

Coins have been carried for luck for centuries and sometimes those coins were accidentally spent. In Great Britain it became common to mark the coin so this would not happen. As a result, “benders” were fashioned. The coin was twice bent, one side up and the other side down. This made it easy to both see and feel to distinguish it from other pocket change. Some benders marked a vow that was taken and others were tokens of affection or luck.

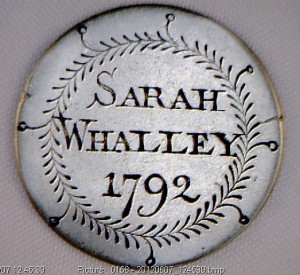

In Great Britain, soon the practice of engraving the coin took hold during the late 1600’s through the 1700’s. Some of these coins are primitively engraved while others appear quite skillful. They were probably made by a mix of skilled artisans as well as average individuals. In fact a unique style evolved called “pinpunching”. This could be done by anyone, but it did take manual skills, practice, and concentration to do it well. Pinpunching involved a sharp pointed metal instrument and something to pound with. The words and images were accomplished through pounding a series of dots…there was no actual engraving. These pin punched coins are fairly scarce.

Many of the early English engraved coins have a quality like scrimshaw…having a simple linear design. The later American love tokens (1800’s) were engraved by skilled engravers with access to multiple types of gravers that created fancy bevels, diamond cut appearances, and texture through liner tools (used for creating multiple parallel lines and crosshatching). The earlier English style is more akin to folk art.

Many of the early English engraved coins have a quality like scrimshaw…having a simple linear design. The later American love tokens (1800’s) were engraved by skilled engravers with access to multiple types of gravers that created fancy bevels, diamond cut appearances, and texture through liner tools (used for creating multiple parallel lines and crosshatching). The earlier English style is more akin to folk art.

Another difference is that in England, these coins are called engraved coins and not love tokens. They were more commonly made to mark births, deaths, unions, and marriages. One will also find more people and portraits on the early English coins. They range from quaint folk art to photo realism reminiscent of Hogarth’s engravings (1697-1764 printmaker/master engraver of book plate images).

Unique to Great Britain are the prisoner tokens. They were engraved by those being shipped off to the penal colonies in Australia. Some will mention the name of the imprisoned and the number of years to be served and others have broad more vague references. A classic engraving is: “When this you see, remember me.” If one can establish that the coin truly is a prisoner token, they are tremendously more valuable than the regular engraved coins. There has actually been a book written just on prisoner tokens.

Unique to Great Britain are the prisoner tokens. They were engraved by those being shipped off to the penal colonies in Australia. Some will mention the name of the imprisoned and the number of years to be served and others have broad more vague references. A classic engraving is: “When this you see, remember me.” If one can establish that the coin truly is a prisoner token, they are tremendously more valuable than the regular engraved coins. There has actually been a book written just on prisoner tokens.

The majority of early English engraved coins are on copper coins. The coins are generally well smoothed on both sides with well rounded edges. They have the appearance of being pocket worn smooth prior to engraving. It is not known exactly how they got to this state. If they had been lathed, they would have crisp sharp edges. They were most likely sanded down by hand. Even ones engraved just on one side, often are smoothed on both sides. Finding one with the coin image in tact or a silver coin is less common. There are also early engravings from other European countries but the practice was most prevalent in Great Britain.

Many U.S. collectors focus on American love tokens for their collections. Some are geared this way especially if they have come from a coin collecting background. Also, the early English counterparts are not frequently seen in the U.S. so in part it is hard to add them to a collection. And, in recent years they have appreciated and out cost their U.S. counterparts. One possible drawback to them is that the copper turns dark with age and it is difficult sometimes to see the engraving as a result. Some people add talc to the surface which lodges in the engraved lines. The contrast of the white on dark brown is both easier to view and photograph. Folk art collectors and historians may in fact prefer these earlier charming coins.